Like every true love, that of the reader is blind. — Jhumpa Lahiri

On The Clothing of Books by Jhumpa Lahiri

It was in her family visits to Calcutta, where uniformed schoolchildren swarmed the busy streets, that author Jhumpa Lahiri first became interested in clothing. Not clothing as an expression of personality or a reflection of a keen sense of style, but as a tool to either blend in or stand out.

The same, says Lahiri, can be said for book covers.

In The Clothing of Books, an 80-page title that could fit in your jeans pocket, Lahiri expresses her stolid relationship to book covers, saying her reactions to those of her own books are “various, visceral.” And not always great.

“They depress me, they confuse me, they infuriate me,” she says. Even a Pulitzer Prize-winning author like Jhumpa Lahiri does not get the final say when it comes to the covers that clothe her books.

But let’s go back to the uniforms in Calcutta, which indicated the school a student attended. This sense of belonging was something Lahiri didn’t have in her own country. And to that point, which country was her “own?” Was it England, where she was born? The U.S., where her Bengali parents eventually moved the family? It wasn’t India, where she’s never lived, nor was it Italy, a place, decades later, she came to call home — but a country which she couldn’t claim as her own.

In Lahiri’s nonfiction books, including In Other Words and Translating Myself and Others, she speaks freely about this schism she’s long been confronted with. And in The Clothing of Books, she uses a tactile analogy to illustrate how she’s felt her entire life.

“I learned the hard way that how we dress, like the language we speak and the food we eat, expresses our identity, our culture, our sense of belonging.”

As a child of immigrants who shopped economically, Lahiri was teased for her wardrobe. Clothing for her became a source of anguish, and she recalls being tormented by the need to choose her clothing before attending her public school. A uniform like her cousins’ in Calcutta interested her immensely.

Lahiri’s ambivalence and, in some cases, distaste, extends to book covers. For a publishing house, a cover signals the arrival of the book. “For me it is a farewell,” she says; the end of her creativity connected to a given project.

Why do covers exist?

“First and foremost,” Lahiri says, covers exist “to enclose the pages.” Beyond that, everything else is commercial. In other words, book covers are designed to sell.

“We don’t live in a world in which a cover can simply reflect the sense and style of the book,” but rather, its function is more commercial than aesthetic.

Because of her detachment from her books’ covers, Lahiri opts to read from the bound galleys of her books while doing readings. She says when forced to use a copy of the actual book, she removes the jacket because “the dressed book no longer belongs to me.”

When a book is dressed in a cover with blurbs and awards splashed upon the front, the first words a reader consumes are not that of the author, but of others. Lahiri doesn’t like this, and I can see her point.

“As soon as the book puts on a jacket, the book acquires a new personality. It says something even before being read, just as clothes say something about us before we speak.”

Thinking back to her cousins’ uniforms in Calcutta, Lahiri says, “I sometimes think, as a writer too, that a uniform would be the answer.”

Book covers as uniforms

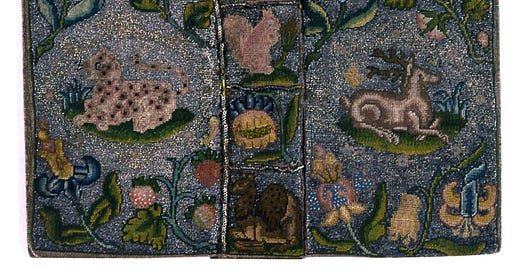

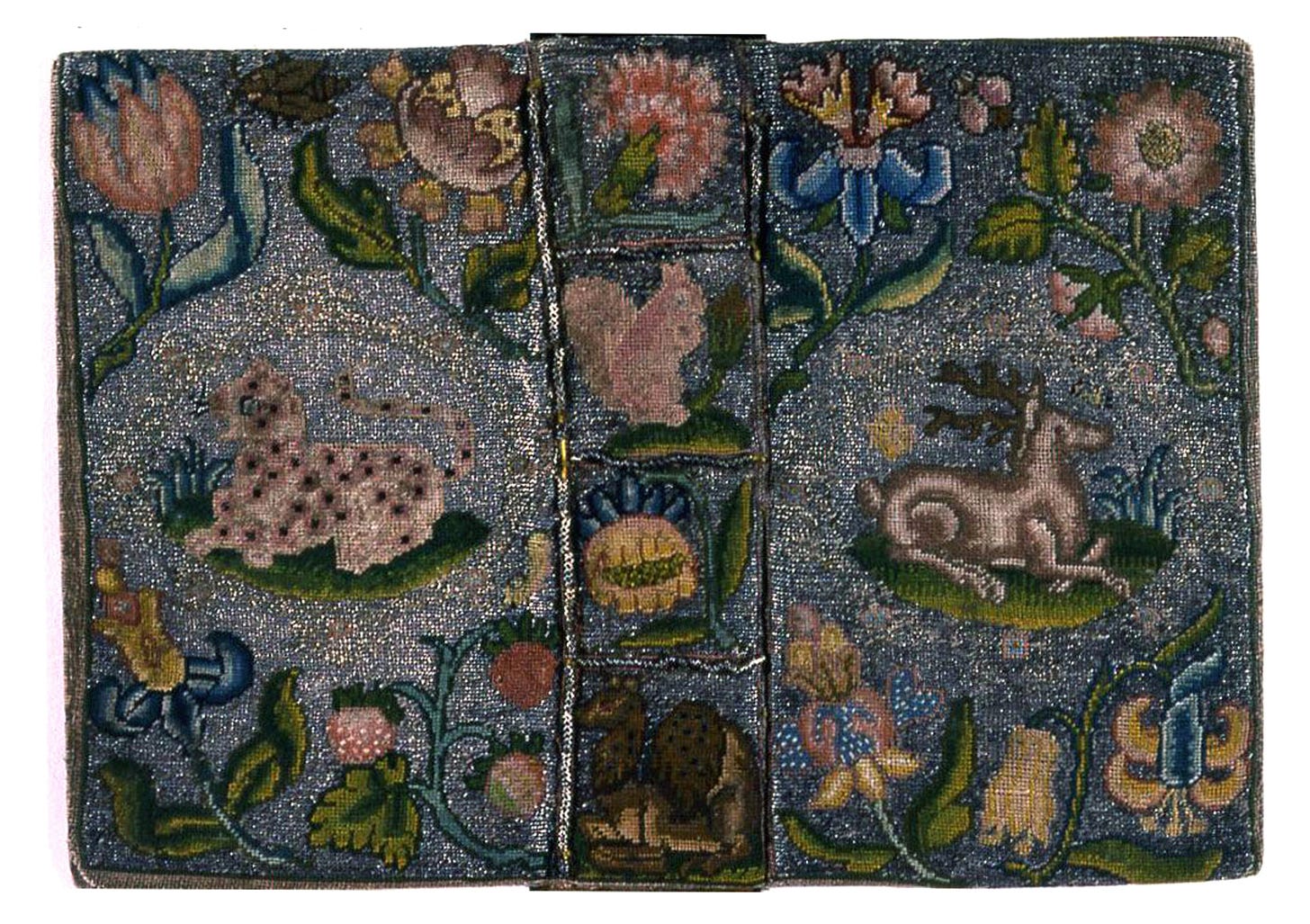

Like the uniformed students in Calcutta who simultaneously had a strong identity and a sort of anonymity, books that belong to an editorial series are seductive to Lahiri.

“I find their simplicity and seriousness admirable,” she says, noting that she can recognize certain series straightaway by their pared-down and cohesive covers. (Think of the black-spine Penguin Classics like this.)

Even when she doesn’t like one of her book covers, which seems often to be the case, Lahiri says she always ends up feeling some affinity for them. “Over time, the covers become a part of me, and I identify with them.”

Her book covers, though wrapped around her words, are not of her choosing. “Upon close inspection, my covers tend perfectly to mirror my own double identity, bifurcated, disputed. As a result they are often projections, conjectures.”

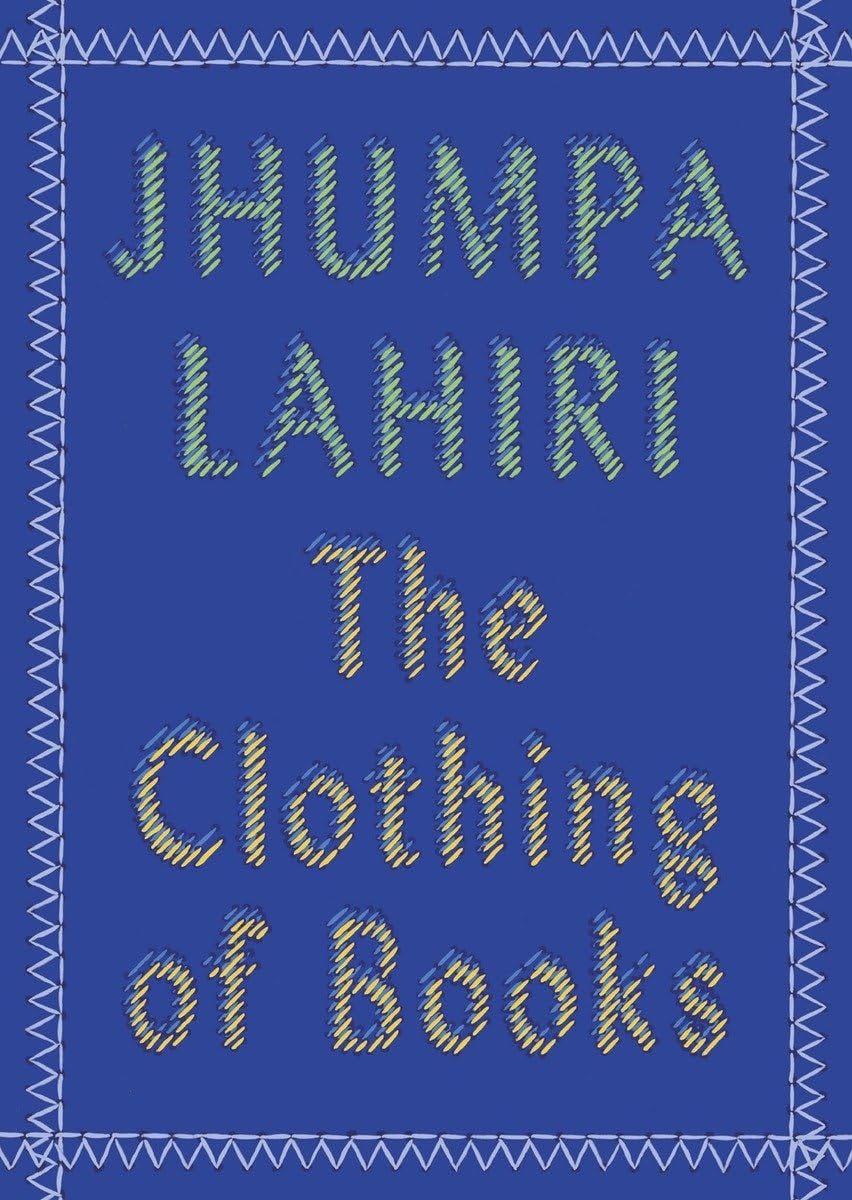

She doesn’t mention whether she approves of the cover for this book, but here’s what the English cover looks like. (She wrote this in Italian — Il vestito dei libri — as a speech she presented for an Italian festival. It was translated into English by her husband, Alberto Vourvoulias-Bush.)

I will leave you with this, my favorite quote not only from this book, but from Lahiri’s entire repertoire:

Like every true love, that of the reader is blind.

— Jhumpa Lahiri

I cannot get enough of this author. Every subject she explores, from Italy to book covers to translation, captivates me. 2024 is my year of Jhumpa, and I am loving it so much. If you want to learn more about Lahiri, her 2015 essay in The New Yorker, “Teach Yourself Italian,” is a gorgeous read about her three-year exile to Italy a decade-ish ago.

What I’m reading: Shame on You: How to Be a Woman in the Age of Mortification by Melissa Petro

What are you reading?

Love,

Words on Words is a free newsletter about books that hits inboxes on Thursdays. Subscription upgrades exist so readers can support my work if they feel compelled, but these weekly essays are free.

Note: When you purchase books through my links, you support Words on Words (I get credits for more books!) and an indie bookstore of your choice at no additional cost to you.

This is my first time hearing about this author. I would love to read her work.

Went to a private school, wore uniform, always felt like I fit in.

Rereading "The Awakening" by Kate Chopin, a book every woman should read.