Every single thing I have created worth a damn has been a practice of love, healing, and redemption. I know this process to be divine. — Melissa Febos

A love letter to those who use writing to process and, ultimately, transform.

Hello! Welcome back to Words on Words, where readers discuss what we love about literature. I am writing to you from the AWP Conference and Bookfair in Kansas City!

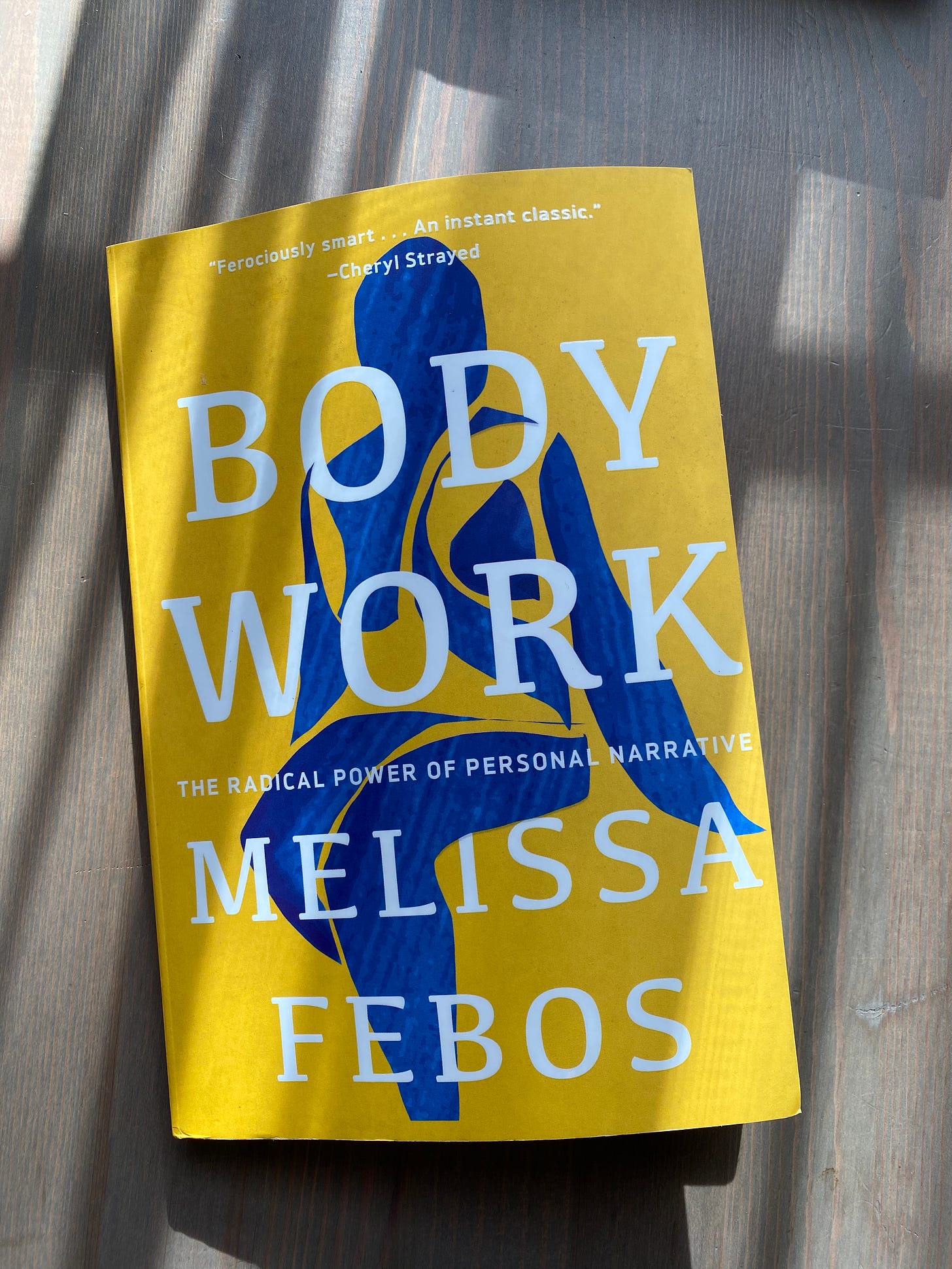

Today we’re taking a look at Body Work: The Radical Power of Personal Narrative by

, who I consider to be one of today’s greatest nonfiction writers.Without knowing it was a craft book on writing, I ordered Body Work: The Radical Power of Personal Narrative from Bookshop.org because it was written by Melissa Febos. That’s all I needed to know about that. (I don’t read jacket copy unless I have to. Given the author of this book, I didn’t have to. The subtitle could have tipped me off to its content, however.)

Melissa Febos is the author of Whip Smart, her debut memoir about spending two years as a dominatrix in her 20s; plus Abandon Me, Girlhood, and her most recent, Body Work. She writes with a candor that reveals so much truth it feels transcendent. It’s not just that her writing is good — which, wow, it’s incredible. But her stories of adolescence are unbelievable; believable only in that we know this masterful author is the one telling us, and therefore we equate it to absolute truth.

Imagine my delight when I opened this book and realized it was a series of essays about writing. But not just that — essays about how powerful the act of writing is; how transformative it can be to write about your past; your sometimes ugly, sometimes harrowing path that brought you to this very moment in time, reading this newsletter.

In her author note, Febos says, “While I sometimes resist the work of writing, I resist my own psychic suffering more, and writing has become for me a primary means of digesting and integrating my experiences and thereby reducing the pains of living, or if not, at least making them useful to myself and others.”

I adore those words, “I resist my own psychic suffering more.” Perhaps I adore them because I understand myself how powerful writing is. As a young girl, I was a devoted diarist. I wrote about all that ailed me, letting the words spill out of me so as to transfer some of the weight from my heart to the page.

I am fairly outspoken about my absentee father, which many may consider a taboo topic. I think the reason I am so open about it is because I spent a lot of my youth, and, if I’m being honest, a lot of my life writing about him. The gaping absence of this person carved out space for something I couldn’t live without: writing.

As it turns out, I can live without him; I have my whole life. But writing? Not a chance.

In Body Work, Febos shares four essays about memoir and what it means to write about our most intimate realities. “Expressive writing about trauma strengthens the immune system, decreases obsessive thinking, and contributes to the overall health of the writers,” Febos says in her first essay, In Praise of Navel-Gazing.

I didn’t consciously know this when I was young, but I am positive my body did. I know something beyond just writing occurred when my pen met the paper; some divine process taking my suffering and metamorphosing it into something upon which to draw inspiration; maybe even healing.

Febos feels similarly:

“Transforming my secrets into art has transformed me. I believe that stories like these have the power to transform the world. That is the point of literature.”

When we write about [insert your own personal brand of trauma], we undergo a powerful transformation. With the wisdom that comes with distance also comes the ability to pick apart what really happened to you. And in the process, you become a different person — quite literally just by writing about it. This is true whether you share your words or not; whether you deem yourself a writer or not.

When I was young, I never shared what I wrote about my father; that wasn’t the point. The point was to process. The point was to interrogate my past to help me decide on my future. Or, as Febos puts it, to grieve and take responsibility. To revise the story of my victimhood and my culpability.

I know now that my openness about my father may be considered taboo because of how it makes people feel. Febos says, “the dominant culture tells us that we shouldn’t write about our wounds and their healing because people are fatigued by stories about trauma? No. We have been discouraged from writing about it because it makes people uncomfortable.”

That’s it — that is exactly what it is. Hearing a woman’s stories of abandonment puts others ill at ease. So, conventional wisdom (and oppression) says we must keep those stories close to our hearts. But: no. We must share these stories primarily because they are healing for us, but also because we never know who they will touch; who else they may help heal.

While reading this book, I thought a lot about the writer

and what she calls embodied writing. She says, “We all live in bodies, and we perceive the world through our bodily sensations. Our physical selves, and our ability to perceive through the physical self, holds the key to writing that stands apart. Writing that is capable of both holding and revealing truth.”To access this truth-telling, Ouellette talks about tapping into your bodily sensations and uncovering “stored stories.” I’d venture to guess that Febos has a similar way of accessing those stories suppressed deep within her.

In her final essay The Return, Febos confronts religion and spirituality:

“I have found a church in art, a form of work that is also a form of worship — it is a means of understanding myself, all my past selves, and all of you as beloved.”

Many go to church in search of comfort and solace, and that can be a wonderful thing. For others, like Febos, the process of writing can be equally as spiritual and transformative.

I will leave you with one more note from Febos about the radical power of personal narrative:

“On the page, I undergo a change of heart, I return to the past and make something new from it, I forgive myself and am freed from old harms, I return to love and am blessed with more than enough to give away. Every single thing I have created worth a damn has been a practice of love, healing, and redemption. I know this process to be divine.”

Melissa Febos, I should mention, is also at this conference in Kansas City! Will the universe allow us to cross paths? I will let you know if so.

If you enjoyed this post, please share it with someone!

What I’m reading: Brass: A Novel by Xhenet Aliu, Call Up the Waters by Amber Caron, and Before and After the Book Deal by Courtney Maum, which is my first re-read of 2024.

What I’m listening to: Alice Sadie Celine by Sarah Blakely-Cartwright

What are you reading? Listening to? Loving? Thank you for reading! Love,

Words on Words is a free newsletter about books that hits inboxes on Thursdays. Subscription upgrades exist so readers can support my work if they feel compelled, but these weekly essays — and everything I write as of now — are free.

Note: When you purchase books from my Bookshop.org affiliate page, you support the author of the book, an indie bookstore of your choice, and Words on Words (I get credits for more books!) at no additional cost to you.

I just found you via @Subsrtackwritersatwork and found this essay. My copy of Body Work just arrived yesterday! I haven't even cracked the cover yet ( life!) but now I am more excited to begin having read your post. My absentee parent was my mother and I have grown more and more vocal about it for the reasons you mention. I find the more I speak of her and my story, the more people reach out and say... me, too.. and thank you. This is powerful work we share! <3

Melissa Febos is the real deal. This book is my bible. The end.