I have already lost touch with a couple people I used to be. — Joan Didion on keeping a personal notebook

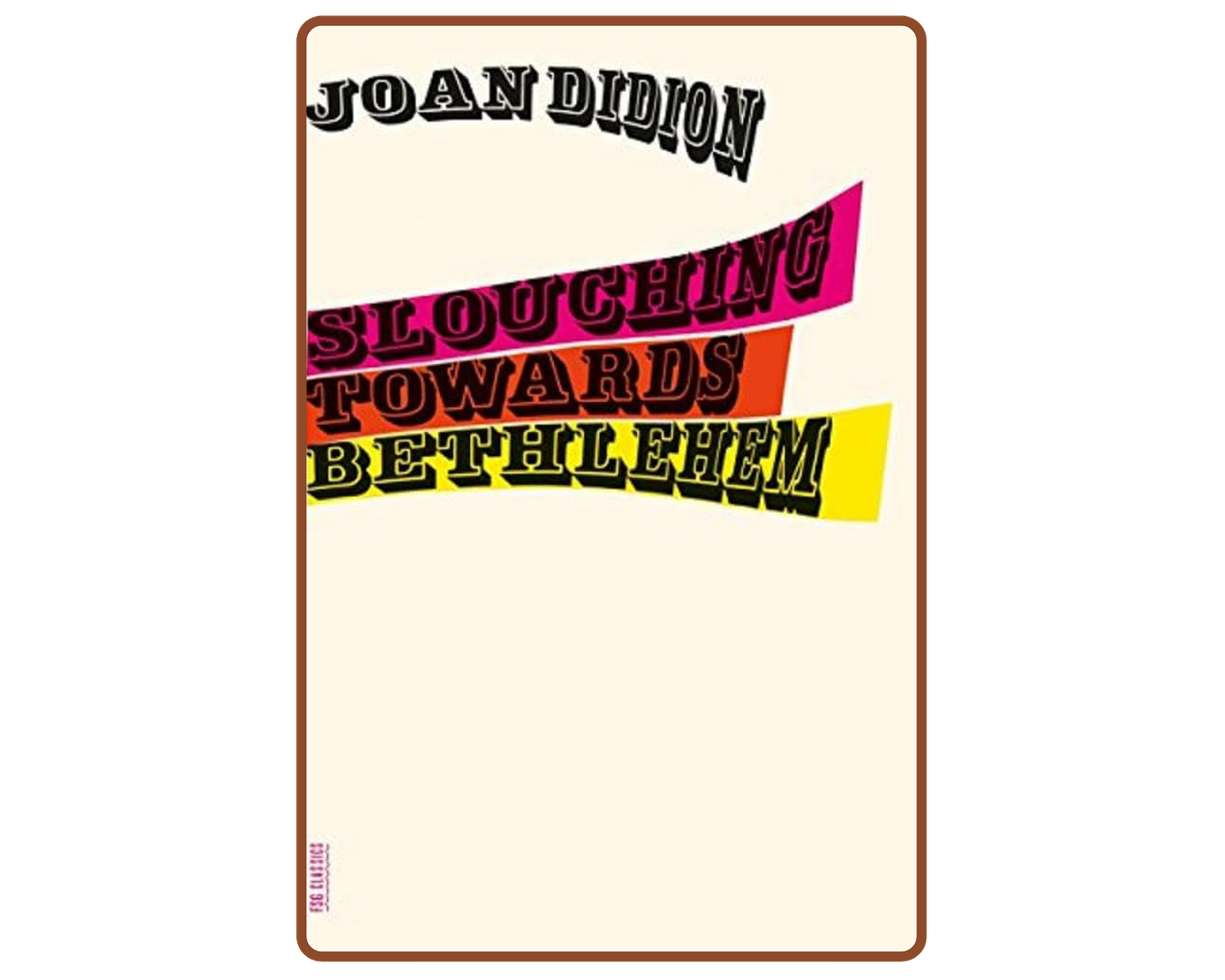

From Didion's collection of essays, Slouching Towards Bethlehem

A commonplace book. You’ve heard of one. You might even have one. It’s the place you write down quotes and beautiful passages, conversations you overhear in line for your coffee, sentences you don’t want to forget but ultimately will until you revisit your notes months, years, decades later.

I’ve kept many over the years, and while I’ve always intended to use them as proper commonplace books with notes about the world around me, every one of them somehow turn into journals; places I end up recording things like how my writing is going or, in the past — how my relationships were faring.

Joan Didion had a better idea of what a commonplace book was for. In Slouching Towards Bethlehem, her collection of essays published in 1968, Didion included an essay called On Keeping a Notebook. It opens with an observation Didion had recorded in — was it 1960? 1961? — she hadn’t included the date in her note.

“That woman Estelle is partly the reason why George Sharp and I are separated today,” the essay begins. It’s a quote Didion overheard, and it’s followed by environmental details: “dirty crepe-de-Chine wrapper, hotel bar, Wilmington RR, 9:45 am. August Monday morning.”

Didion found this in her notebook years later. Why had she written about that woman Estelle and George Sharp? She remembers being in Wilmington, though she doesn’t remember why. She recalls the woman, the one now separated from George Sharp, who was wearing a plaid silk dress with the hem coming down.

In the essay, Didion questions why she wrote it down.

In order to remember, of course, but exactly what was it I wanted to remember? How much of it actually happened? Did any of it? Why do I keep a notebook at all?

Didion was five years old when she received her first notebook. It was a Big Five tablet given to her by her mother with the “sensible suggestion that I stop whining and learn to amuse myself by writing down my thoughts.”

So she wrote down her thoughts.

But it’s what she did with those records of time and place that I am interested in, because she didn’t write down the day’s events (when she tried to do that, boredom had so overcome her that the results were “mysterious at best”) and she instead copied down what she, in this essay, called lies. The cracked crab she wrote about one day in 1945, the day her father came home from Detroit, for example. Didion says she was ten years old when she wrote about it and would not now remember the crab. “The day’s events did not turn on cracked crab. And yet it is precisely that fictitious crab that makes me see the afternoon all over again, a home movie run all too often, the father bearing gifts, the child weeping, an exercise in family love and guilt.”

With the notes she recorded in her personal notebooks, Didion captured how specific situations felt to her; what it was to be her. “That is always the point,” Didion says. To preserve the person she was at the time of recording, not by writing down what happened to her but instead memorializing what caught her attention; how her surroundings felt to her then.

The essay interrogates some of her notes: “What exactly did I have in mind when I noted down that it cost the father of someone I know $650 a month to light the place on the Hudson in which he lived before the Crash?” Adding, “does not the relevance of these notes seem marginal at best?” and “what kind of magpie keeps this notebook?”

But she gets to the point: she didn’t copy down facts and conversations she overheard to use the lines in her work but rather to remember the woman who said it the afternoon Didion heard it; to recall the California winter sun out on the terrace, and later, the low-grade afternoon hangover, the black snake she ran over on the way to the supermarket.

“How it felt to me: that is getting closer to the truth about a notebook,” she says. These recorded tidbits helped the older Didion access the many different feels of her past selves.

“I think we are well advised to keep on nodding terms with the people we used to be, whether we find them attractive company or not. Otherwise they turn up unannounced and surprise us, come hammering on the mind’s door at 4 a.m. of a bad night and demand to know who deserted them, who betrayed them, who is going to make amends. We forget all too soon the things we thought we could never forget. We forget the loves and the betrayals alike, forget what we whispered and what we screamed, forget who we were.”

Inside those notebooks are the many lives Joan Didion lived; the people with whom she intended to keep in touch so they didn’t visit her at 4 a.m. of a bad night. They weren’t snippets she could pull from for use in her books, which is what, until I read this essay, I had thought writers used personal notebooks for: inspiration and ideas; a well of creativity to drop the bucket into and heft it up when needed.

But to think about notebooks as a way to keep on nodding terms with those we used to be? It’s gorgeous. It sends chills down my spine.

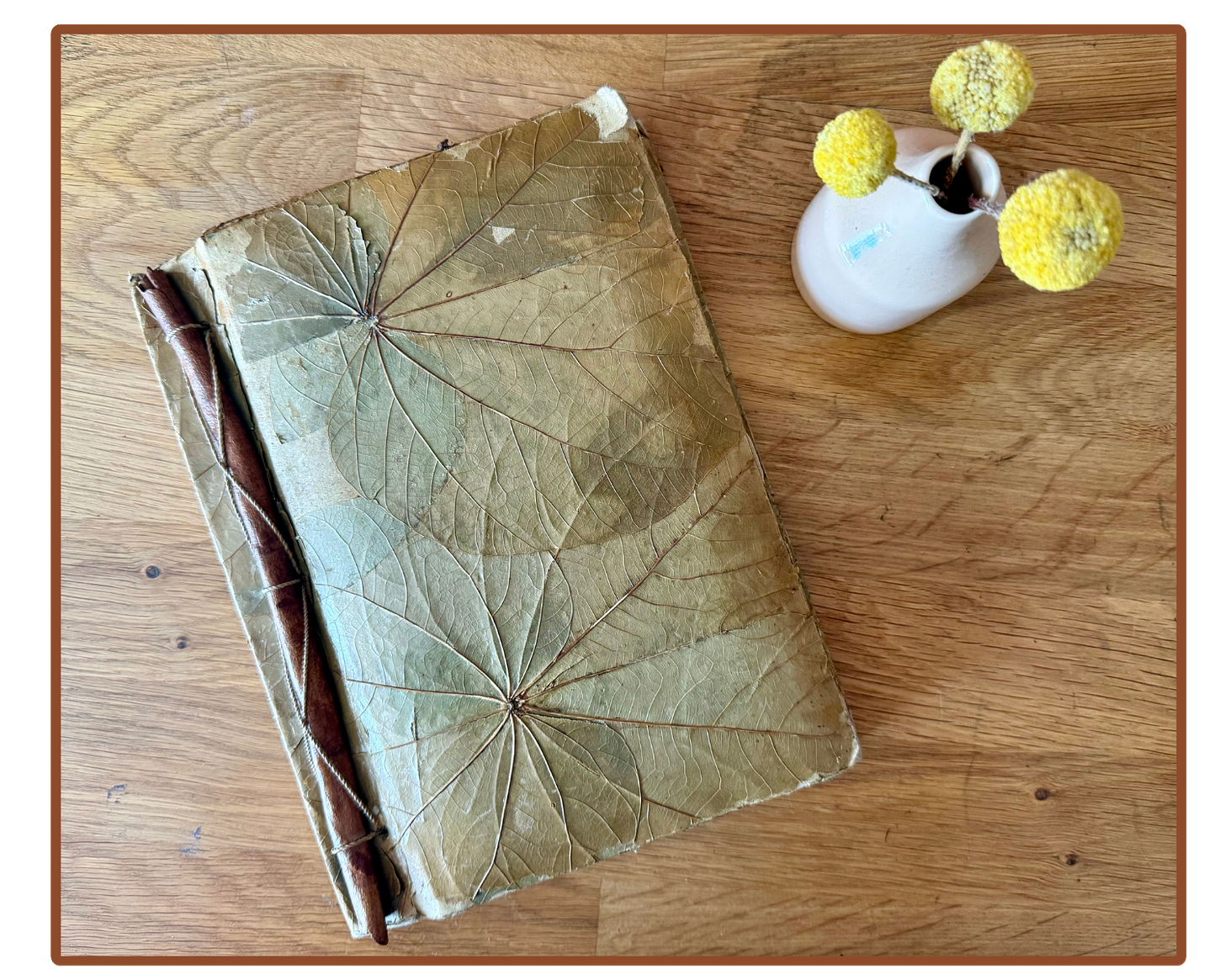

I find a journal I carried on and off between 2006 and 2010, the brittle leaves adorning the cover chipped at the corners, the thick unlined paper pretentious and gaudy, more like a paper towel than something to preserve history on. I brought the notebook with me to San Diego once. Inside is a newspaper cutout of the weekend temperatures in the United States. San Diego, reliably warm and sunny, was cooler than Minnesota, where I flew in from. I see this cutout and I remember the type of person I was then: I straightened my long highlighted hair. I sunbathed unabashedly, wearing sun tan oil rather than the 50 SPF I use now. I cared that Minnesota was going through a heat wave and San Diego was only in the 70s.

I remember her. I nod to her.

We don’t learn what Didion’s notebooks looked like. We don’t see any pictures like we would if she were a woman of the internet. I envision her writing with pencils, perpetually dull from use. I picture a doctor’s hand, sloppy and decipherable only to her.

English professor

keeps a newsletter dedicated entirely to notebooks and note-taking, studying the world’s best note-takers. It’s called Noted, and for the two-year anniversary of her publication, she shared 12 readers’ methods for organizing their quotes. The art therein is exquisite; it’s unlike what I picture Didion’s; very much unlike the notebooks I keep, but very much like I always thought my notebooks would look.Beautiful or not, my personal notebooks provide me with something meaningful, bringing me back to the way it felt to be the version of myself that ripped the weather map out of the newspaper and filed it in my journal so that later, back in Minnesota, I would glue it in, bringing me back to the two queen beds in the dark hotel room, the heavy curtains despicably blocking the desert sun.

“I have already lost touch with a couple people I used to be,” Didion says. So, too, have I. I nod to the people I once was, and I carry on leaving bread crumbs in my notebook of who I am today.

This essay is a part of The Joan Didion Group Project,

’s month-long study of one of America’s most iconic writers.For more reading on Joan Didion, I recommend:

A week in my life as a Joan Didion superfan by

Allison Bornstein Decodes Joan Didion's timeless style by

What are you reading? Have you read any Didion? Do you keep a commonplace notebook? I want to hear about it if so!

What I’m reading: The God of the Woods by Liz Moore (a thousand thanks to

for sending me a copy of this!)Love,

Words on Words is a free newsletter about books that hits inboxes on Thursdays. Subscription upgrades exist so readers can support my work if they feel compelled, but my weekly essays are free.

When you purchase books through my links, you support Words on Words (I get credits for more books) and an indie bookstore of your choice at no additional cost to you.

Joan Didion AND notebooks are my two favorite subjects. LOL

I have had a consistent journaling practice since 2019... and I have a stack of those. But I am so curious about Commonplace notebooks... because those are so different from the kind of whiney writing that I have established.

I just really love the idea of keeping a notebook that is about books, art, culture, ideas... I even bought a journal this past weekend... I don't think I can commit to consistently writing down quotes... but maybe I can write down my MOST favorite quote of each book? I would love to have a stack like that to give to my daughter when she is a little older.

Thank you for playing and for inspiring me to make some decisions about NOTEBOOKS!!!

Love this and how you compare it to your own notebook keeping! I remember first reading this Didion essay and thinking the same as you: my notebooks have never looked like this. You can really get a sense of her writing style from her notes.

I am ashamed to admit that I throw away my notebooks the minute I get to the last page, so I can't reflect back on the person I used to be...